Scratching the Surface of the Doomed Franklin Expedition

The mystery of the Franklin expedition is one of the most pervasive stories in naval history. Commissioned by the British Royal Navy in the 1840s to find the fabled Northwest Passage, the crew and officers disappeared in what is now known as the Canadian Arctic – and were never heard from again.

Sir John Franklin: The Navy’s Last Choice

In the Victorian era, it was widely believed that a Northwest Passage existed. The goal was to find a water route through the Arctic that connected the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean as a possible trade route to Asia. The Franklin expedition was one of many unsuccessful European attempts to find it. In 1845, 59-year-old Captain Sir John Franklin was selected to lead the expedition – after at least four preferred choices either turned the voyage down or were ruled out. With 129 men on board between the ships HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, Franklin commanded the voyage across the Atlantic. It was the best-equipped, most technologically advanced Arctic expedition yet.

But it wasn’t long before Franklin was dead and the surviving men were deserting the ships to head south.

From left: Daguerreotypes of Francis Crozier, Sir John Franklin, and James Fitzjames, taken by photographer Richard Beard just before they led the disastrous expedition. Photos: Wikimedia Commons

When they first set sail, Franklin and his fellow officers Francis Crozier (Captain of HMS Terror) and James Fitzjames (Captain of HMS Erebus) had reason to believe they would reach the Arctic in no time. The ships’ bows had been reinforced with sheet iron to withstand ice; steam engines were added in case of emergency. The crew had provisions for three years, and desalinators on the ships could purify seawater for drinking.

But disaster first took hold in 1846 when the ships got frozen in ice off King William Island, despite the fact that they had been fitted for Arctic travel. The ice floes did not recede even during summer, so the ships were forced to spend winter stuck in the ice. Franklin died of unknown causes in June of 1847, along with 24 other crew members by that time. Years later, the discovery of stashed written messages would reveal that the surviving sailors abandoned the ships in April 1848 (after one year and seven months trapped in the ice) to journey south to the mainland – on foot.

Ultimately, there would be no survivors, and very few traces of what had happened.

The British Search for the Ships

Back in England, the British Admiralty and Lady Franklin sponsored some 30 expeditions to search for the lost crew for over a decade after they had seemingly vanished. Searches were unsuccessful, given that the ships sank before any Europeans could ever find them. However, one of the search expeditions was credited with the first recorded European “discovery” of the Northwest Passage – Irish explorer Robert McClure found and transited the waterways while looking for Franklin and his crew in 1850.

Although none of the voyages in the 19th and early 20th centuries found the lost ships or any surviving crew members, they did learn enough to gauge a general picture of what had happened. They owed their discoveries to the testimony of Inuit whose traditional lands make up the territory of Nunavut (which was eventually named part of Canada due to British colonisation).

Invaluable Inuit Testimony

In 1854, a number of Inuit told British explorers of 35 to 40 white men who had died of starvation near the mouth of the Back River. Other Inuit confirmed the testimony; they showed explorer John Rae some objects associated with the expedition, including silverware belonging to the senior officers. Inuit also shared reports of cannibalism among the increasingly desperate crew members. Rae passed these findings on to the Royal Navy in England, where the cannibalism claims shocked Victorian society. Lady Franklin, Charles Dickens, and other prominent figures refused to entertain the possibility, but evidence uncovered over the following years would substantiate the claims. Overall, historians would not know much about the context of the naval disaster were it not for Inuit who provided their knowledge all those years ago, and have done so ever since.

HMS Erebus and HMS Terror in 1845. Photo: The Illustrated London News

While the story had become clearer with each search expedition, there was still no trace of the ships Erebus and Terror. Inuit testimonies would again lead to further breakthroughs; they told European explorers of the last place they had ever seen the ships, specifying a much smaller area of the vast Arctic and thTerrorus narrowing the search.

During ongoing attempts to discover the shipwrecks, expeditions still sought to learn what happened to the crew. In 1859, not long after the rumours of cannibalism reached England, a lieutenant on the McClintock voyage, William Hobson, found a note hidden in a cairn on the northwest coast of King William Island. There were two parts to the note – the first was from May of 1847, stating all was well; the second was dated April 1848 and carried news of Franklin’s death. It was signed by Fitzjames and Crozier, who were left in charge, and documented the crew’s intent to abandon the frozen ships and walk south.

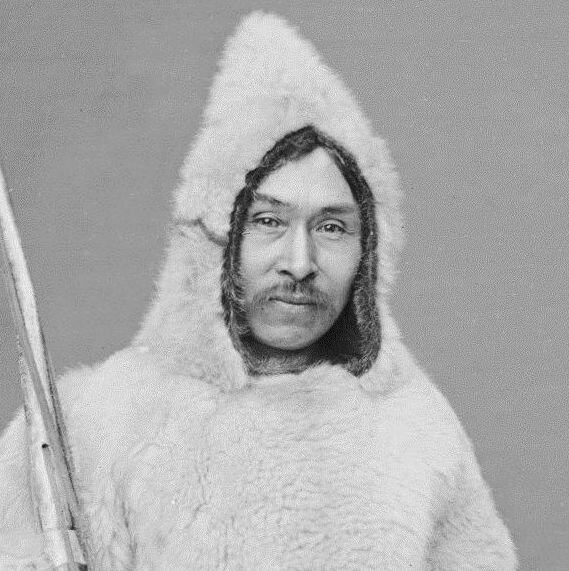

Ipirvik and his wife Taqullituq were well-known and widely travelled in the 1860s and 1870s. Photo: T.W. Smillie / Smithsonian Institute Libraries

In the years to follow, Inuit continued to show British explorers evidence of the failed voyage by way of graves they had come across, including human remains, camps, relics, and other items. Explorers also found skeletons and abandoned equipment; the remains were taken to England and examined with hopes of identifying them. Ipirvik and Taqullituq, who were Inuit guides to Charles Francis Hall, collected hundreds of pages of Inuit testimony alongside him. Historians were still researching this testimony in-depth by the end of the 20 th century, doggedly trying to solve the mystery.

Archaeological Discoveries

Archaeological excavations took place between 1981-1982, led by Dr. Owen Beattie of the University of Alberta. Analysis of human remains found Vitamin C deficiency (scurvy), high levels of lead in the sailors’ bones, and cut marks on the bones that were strongly indicative of cannibalism. A cause of death could not be pinpointed, however. At that point it was known that there were three crewmen’s graves on Beechey Island, and in 1984, Beattie obtained legal permission to exhume the bodies and perform autopsies.

The bodies of John Torrington, John Hartnell, and William Braine were exhumed – almost perfectly preserved by ice. Tissue and bone samples were analyzed to conclude that pneumonia had been the cause of death, with lead poisoning a contributing factor (although the cause and impact of the lead exposures are disputed).

The graves of crew members John Torrington, John Hartnell, and William Braine on Beechey Island in Nunavut, Canada. The fourth grave is for Thomas Morgan, a sailor who died during a later Franklin search expedition. Photo: Gordon Leggett / Wikimedia Commons

Finding the Lost Ships

Attempts to find the two shipwrecks continued until 2014, when Parks Canada found the HMS Erebus in relatively good condition. Undisturbed for almost 170 years, it lies under 11 metres of water at the bottom of Wilmot and Crampton Bay. It has deteriorated significantly since its discovery due to storms and water pressure displacing it.

In 2016, a Canadian non-profit called the Arctic Research Foundation announced the discovery of the HMS Terror, its condition pristine. A 1997 agreement between the British government and Canada had the British agreeing to transfer the wrecks to Canada once found, and their locations (nearby each other) are now a National Historic Site, the first to be co-managed by Inuit and Parks Canada.

Although a victory, the discovery of the shipwrecks brings even more questions. The resting position of both ships suggests one or even both of them may have been re-manned after their abandonment, as they were found some distance from where they had been locked in the ice – though this hypothesis has not been proven. There is an urgency to collect more evidence from the shipwrecks due to risks of deterioration. In collaboration between the Inuit Heritage Trust and Parks Canada, underwater archaeology crews hope to find ship’s logs or other documents that may shed more light on the Franklin story. However, the unpredictable Arctic weather means they can only dive in August and September each year.

The Franklin expedition is an enduring source of fascination among historians and hobbyists alike, with a fictionalised account in the form of Dan Simmons’ 2007 novel The Terror, and a 2018 AMC television series of the same name. The continuing search for answers has enshrined the failed expedition in myth. The disaster also demonstrates the weight and significance of Indigenous oral testimonies, which were pivotal to many of the discoveries to date. The undeniable fact of the story is the feeling of great loss. Historians and archaeologists may never find Sir John Franklin’s body or those of the other crew members – and it is unknown what might be learned if they did – but the mystery will continue to captivate no matter what comes to light.

Serena Ypelaar is the Founder and Editor-in-Chief of The Mindful Rambler, a literary and historical interpretation blog. Born and raised in Toronto, Canada, she has a formal background in colonial history, museum studies, and literary biography. To find out more about The Mindful Rambler or to get in touch, visit the blog or follow us on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter.

Further Resources:

Wrecks of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror National Historic Site (Canada)