Stand Watie: The Last Confederate General

Colorized photo of Stand Watie circa 1865

In the history of the Civil War, many stories have been told—many accounts of unknown men and women who fought for the Union and the Confederacy. Nevertheless, sometimes, stories get lost and are almost forgotten in history. However, in some rare cases, their exploits survive, and which time tell the story of who they were and what they hoped to achieve. This is the story of one Confederate Brigader General who fought for himself and his people. This is the story of Cherokee Indian Stand Watie.

Stand Watie was born in 1806 into an affluent Cherokee family in Oothcaloga (near present-day Rome, Georgia). He was given the Christian name Isaac S Watie whereas his real name was Degadoga, or "He Stands." Born into a mixed family, he went to Brainerd, a Moravian mission school on the Georgia-Tennessee border. He developed a talent for writing persuasive political tracts and convincing letters. Because of family status, Stand was able to get a job working as a clerk in the Cherokee court and thus earning his license to practice law.

Since Watie was a member of the mix-blood elite, he openly favored removal to the West in the face of intense pressure from settlers. Watie's uncle, Major Ridge, played a prominent role in Cherokee politics during the removal crisis of the 1820s and 1830s, ultimately defying the wishes of the Cherokee Council by advocating removal and signing the Treaty of New Echota in 1835. The treaty of New Echota surrendered the Cherokee's eastern homeland and obligated the tribe to move to the West. This controversial treaty came into conflict with the prominent chief of the Cherokee Nation, John Ross. The animosity between the two individuals heightens after entering Indian TerritoryTerritory. This hatred led to violence, which resulted in Watie's uncle, two brothers, and a cousin being assassinated by Ross supporters for their compliance with the removal policy. Watie escaped and became the lone survivor of Cherokee leaders who supported removal. In Indian Territory, Watie established a thriving plantation on Spavinaw Creek, became a prosperous enslaver, and served as the leader of the mixed-blood faction in the Cherokee Nation. On the eve of the Civil War, Watie organized in Indian Territory a secret organization of supporters of Southern rights known as the Knights of the Golden Circle. At the outbreak of the Civil War, his followers actively worked to bring the Cherokee into the Confederate fold. He often conflicted with John Ross and his followers, who supported neutrality. As a result, the Cherokee Nation was divided.

On July 12, 1861, Stand Watie received a colonel's commission in the Confederate military. He raised a regiment of 300 mixed-bloods and headed toward the northeastern border with Kansas to guard against a possible Federal invasion. He persuaded John Ross to sign a treaty with the Confederacy. Ross signed the treaty of alliance on October 7, 1861, with Special Commissioner Albert Pike of the Confederate Bureau of Indian Affairs. In doing so, Watie's regiment was mustered into a Confederate unit and put into service as the Cherokee Mounted Volunteers. Waite would later change his unit to the cavalry unit, the 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles. Watie operated against Union positions in Missouri, Kansas, Arkansas, and northern Indian Territory. Watie's first objective with his newly created unit was to participate in the pursuit of Opethyelahola's band of loyal Creeks, who were attempting to flee northward to Kansas. On December 26, 1861, at Chustenahlah, Colonel McIntosh, commanding 2,000 from Arkansas, chose to engage Opethyelahola's numerically superior forces. As Federal military operations increased in the region, Indian regiments were being pressed for service in Arkansas, outside the bounds of Indian TerritoryTerritory and violating the treaties. Special Commissioner Pike (who had held the military rank of brigadier general) reluctantly led his force of 1,000 Choctaws, Chickasaws, and Stand Watie's Cherokees into Arkansas. The result of the battle was a Confederate victory. The Natives that did manage to escape died along the way further north. This battle is also known as the Trail of Blood on Ice. An Estimated 2,000 Natives died.

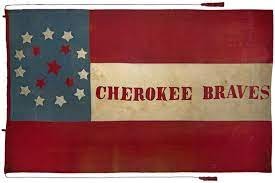

Flag of the Cherokee Braves, Stand Waite’s unit during the Civil War

The battle that would cement Watie in the history books of the civil war was the battle of Pea Ridge in March of 1862—the first of the fighting in Leetown. Rather than attack Gen. Samuel R. Curtis' fortifications, Confederate Gen. Earl Van Dorn proposed to march around the Union right flank and strike the Federals near Elkhorn Tavern. In the course of the maneuver, however, Van Dorn's two wings under Gen. Benjamin McCullough and Gen. Sterling Price were divided and compelled to advance on two roughly parallel roads, separated by Pea Ridge. McCullough's 8,000 Confederates—veterans of Wilson's Creek—marched east on Ford Road, where they were set upon by Federal cavalry under Cyrus Bussey. Bussey's attack bought Union division commander Peter J. Osterhaus precious time to bring up his infantry. While wheeling his troops into position, Gen. McCullough was killed, as was his successor, James McIntosh. Confusion reigned in the Southern ranks. The remaining Confederates—including a brigade of Native Americans under Gen. Albert Pike—attempted to drive off the Federal attack but were checked by the arrival of Jefferson C. Davis' division of Yankee infantry. Without support from Price's troops, the remnants of McCullough's command were forced to withdraw.

The next significant engagement took place at Elkhorn Tavern. On March 7, 1862, the head of Van Dorn's column struck the 24th Missouri near Elkhorn Tavern. Federal infantry of Col. Eugene Carr's division rushed to the aid of the lone regiment but to no avail. Though Van Dorn's cautious deployment of Price's force allowed Carr ample time to reinforce his troops at Elkhorn, the Southerners still held the numerical advantage. Successive waves of Confederate attacks on both Union flanks forced the Yankees to fall back to Ruddick's Field. Late afternoon, Union commander Curtis organized an abortive counterattack in the fading daylight. Though the Confederates had pushed the Yankees, their inability to link up with McCullough's force ultimately denied Van Dorn a complete victory.

The next day, on the morning of March 8, a furious artillery bombardment wrought havoc on the Southern line. Immediately following, Gen. Franz Sigel led a Union assault, driving to the Confederate right. Davis' division soon followed, attacking the center. Lacking ammunition and sufficient artillery support, Van Dorn's Southerners were compelled to withdraw to the Huntsville road, where they could escape past Curtis' right flank. Though the Confederate army had been allowed to escape relatively intact, the Union victory at Pea Ridge solidified Federal control over Missouri for the next two years.

Though the battle ended in a Confederate defeat, Watie's regiment performed relatively well, capturing a Federal battery. By the summer of 1862, many disenchanted and embittered Indian refugees in Kansas joined Union forces. They returned to Indian TerritoryTerritory, determined to take revenge upon the Confederate Cherokees, Creeks, and their allies. Ross went to Washington, arguing that he had no choice but to sign a treaty with the Confederates. The exiled principal chief of the Cherokee Nation then proclaimed Cherokee loyalty to the Union. Stand Watie used the opportunity to declare himself the new head of the Cherokee Nation and consolidated his power. Thus the division of the Cherokees in Indian Territory was complete.

Although Watie and his regiment participated in numerous conventional battles and more minor skirmishes with Federal troops, for the remainder of the war, supporters of each faction still living in the TerritoryTerritory staged hit-and-run campaigns against the other. By the summer of 1863, Confederate hopes for retaining control of Indian Territory vanished. Northwestern Arkansas was in the hands of Federal forces after their strategic victory at Prairie Grove the previous December. United States troops and loyal Indians invaded Indian TerritoryTerritory once again, forcing many pro-Confederate Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole Indians to flee south to the Red River Valley to become refugees among the Chickasaw and Choctaw Nations. In July, Confederate defeats at Gettysburg and Vicksburg dampened hopes for ultimate triumph. Even ardent Confederates like Stand Watie recognized the unlikeliness of a Southern victory in the war. Nevertheless, Watie remained faithful to the alliance for the remainder of the conflict, motivated primarily by the desire to maintain his power within the Cherokee Nation over the supporters of John Ross. On May 6, 1864, in return for his loyalty, Watie was promoted to brigadier general, the only Indian to hold this rank in the Civil War.

Though Stand Watie has often faded out of the Civil War history books, perhaps Watie's most significant military accomplishments occurred in the summer and fall of 1864. On June 15, Watie captured the Federal steamboat J. R. Williams on the Arkansas River with its $ 100,000's worth of supplies, including 150 barrels of flour and 16,000 pounds of bacon. Three months later, in what has been called "the biggest Confederate victory in the Indian Territory," Watie and his men captured a 300-wagon Federal supply train and its $1.5 million's worth of supplies at the second battle of Cabin Creek on September 19, 1864. Though these battles did not affect the war, these acts were deemed "moral victories."

He finally surrendered his command on June 23, 1865, and was the last Confederate general to capitulate. During the Reconstruction era, Watie worked at rehabilitating the Cherokee Nation from the ravages of war and recouping his fortune. One of his most lasting contributions was his effort to congeal ancient tribal factions into a permanent, unified political community. Watie retired from public life and died at his home along Honey Creek on September 9, 1871.

Sources:

“Civil War Virtual Museum | Native Americans in the War | Gallery.” n.d. Www.civilwarvirtualmuseum.org. Accessed April 28, 2023. https://www.civilwarvirtualmuseum.org/1861-1862/native-americans-in-the-war/.

“Battle of Pea Ridge Facts & Summary.” 2008. American Battlefield Trust. December 22, 2008. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/pea-ridge.

“Stand Watie.” n.d. American Battlefield Trust. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/stand-watie.

“Watie, Stand | The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.” n.d. Www.okhistory.org. https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=WA040.